“The future ain’t what it used to be.”

− Yogi Berra, Baseball Hall of Fame Catcher & Manager

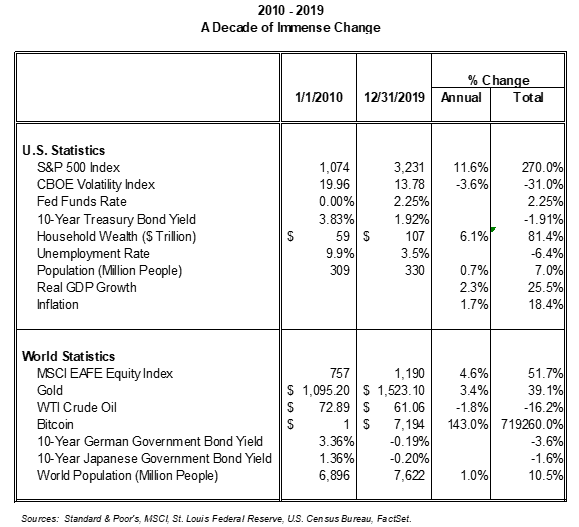

The 2010s represented the longest-ever period of sustained, uninterrupted economic growth and associated market gains. With shrinking unemployment, growing average household wealth, and increasing income disparity – driven by the most activist Federal Reserve in history – the stock market climbed to historic highs and the housing market was resuscitated, as bond yields declined to all-time lows. The economy has experienced 110 months of sequential job gains thus far, and unemployment has reached a 50-year low.

Over this decade of immense change, the United States experienced many fascinating investing phenomena:

The United States lost its AAA credit rating.

Until 2011, the Federal government had always raised the debt ceiling in a collegial, bipartisan manner, so that the Federal government would continue to operate without a hitch. In 2011, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives required spending concessions from President Obama before it would agree to raise the debt ceiling. Although a last-minute deal was eventually reached, the capital markets reacted violently to the negotiations. Accordingly, Standard & Poor’s downgraded the U.S. credit rating for the first time in history, dropping it two notches from AAA to AA+.

“Too Big to Fail” got a whole lot bigger.

During the Financial Crisis, 982 U.S. banks, insurers, and finance companies were deemed to be “Too Big to Fail,” thus justifying unprecedented, massive taxpayer cash bailouts, and an extended period of zero percent interest rates. Despite the risks looming from these large-scale enterprises, the biggest banks have become far larger over the past decade. Today, Citigroup, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo each have more than $2 trillion in total assets.[1] Beyond that, the notional amount of derivatives on the balance sheets of the Too Big To Fail banks, now measured in the hundreds of trillions of dollars, should warrant, in our view, considerably more concern from investors and regulators.

Zero percent and negative interest rates played a critical role in driving asset prices north.

Central banks across the globe ventured into uncharted territory in the past decade by cutting interest rates to zero percent and, in certain countries, below zero percent. The European Central Bank, as well as the central banks of Japan, Sweden, Denmark, and Switzerland cut their respective interest rates into negative territory. For the first time in 5,000 recorded years of economic history, government bonds traded with a negative rate of return. In 2019, Germany issued a 30-year bond with a zero percent yield for the first time. Roughly one-third of non-U.S. bonds now sport a negative rate of return.[2]

Quantitative Easing (QE) played a significant role in stimulating financial asset prices.

In addition to zero percent and negative interest rates, the Federal Reserve and other central banks across the globe purchased trillions of dollars of government bonds, mortgage-backed securities, and, in certain cases, equity ETFs, reducing borrowing costs for governments, corporations, and households alike. U.S. companies issued record levels of corporate debt and used much of the proceeds to repurchase stock. From 2008 to 2015, the Federal Reserve expanded its balance sheet from $800 billion to $4.5 trillion.

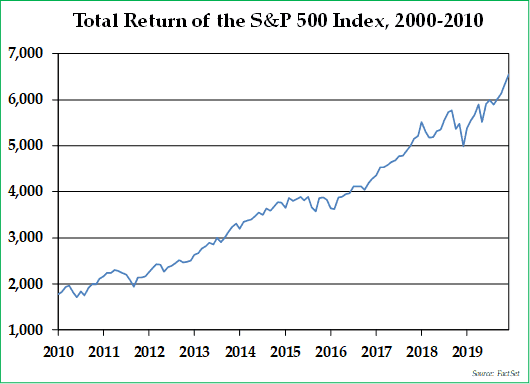

The 2010s represented an uninterrupted bull market.

The decade began and ended in one extended bull market, with record-low interest rates, record-high profit margins, tax cuts, and unconventional monetary policies like quantitative easing pushing the stock prices upward with seemingly no pause in pace. The S&P 500 Index trumped all other global markets this past decade in terms of investment performance with a 270% total return, as demonstrated in the chart below.

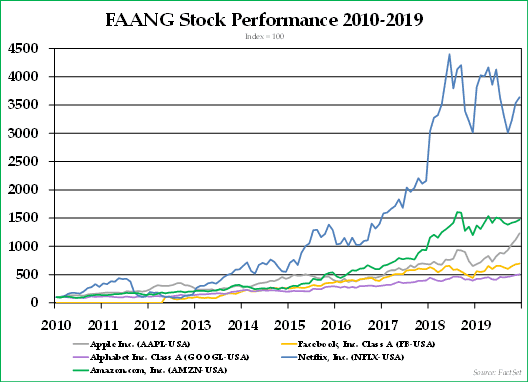

Big tech monopolies formed and outperformed.

Investment performance for the FAANG technology companies (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Alphabet / Google) dominated the performance of the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq Composite; the best performing stock in the 2010s amongst the FAANG stocks was Netflix with a 4,111% total return, and the “worst” performing stock of these six companies was Alphabet with a 432% total return. Notably, the U.S. Department of Justice has not brought an antitrust lawsuit against a technology company since 1999.

Unicorns became rampant.

In financial jargon, a “unicorn” is a privately held startup with a valuation of over $1 billion. Although unicorns are supposed to be creatures only found in fairy tales, there were as many as nearly 300 financial unicorns in 2018.[3] The proliferation of unicorns has been driven by 1) venture capitalists intensely pushing the “get big fast” strategy, 2) richly-priced acquisitions by large corporations who have easy access to cheap money, and 3) the considerable increase in the amount of private capital invested in startups.

Shale oil transforms the U.S. energy industry.

Extracted from oil shale rock fragments, shale oil is now being produced unconventionally in many locations in the United States and elsewhere. While technological advancements increased the amount of unconventional oil and gas reserves in the United States during the 2010s, the costs of extracting shale oil, both in terms of dollars spent and environmental risks, are much higher than the costs of conventional oil production. The lifetime of shale oil wells is also much shorter than that of conventional wells. Nevertheless, this drilling innovation contributed significantly to GDP growth during the 2010s and transformed the United States from a net oil importer to a net oil exporter.

Cryptocurrencies became a new asset class.

While bitcoin was launched in 2008, most Americans were not aware of bitcoin and other digital currencies until 2017 when cryptocurrency prices hit the stratosphere. In fact, bitcoin was the top performing asset class of the 2010s with a whopping price increase of 719,260%. Many investors and technology entrepreneurs remain excited about the long-term potential of cryptocurrencies to revolutionize money, payment systems, and banking.

Globalization began to reverse.

Reversing a decades-long trend, international trade began to decline in 2018. President Trump took aim at the trading policies of the European Union, South Korea, Japan, and, most importantly, China. Since then, billions of dollars of new tariffs have been established, causing increased economic uncertainty. With China alone, the United States has imposed tariffs on $550 billion in Chinese goods, which were countered by $185 billion in tariffs on U.S. exports to China.

An extraordinary decade for the capital markets has just drawn to a close. In the last several weeks, many investment firms and financial media outlets have been making predictions about the year 2020. Instead, we would like to take a stab at making some predictions about the next decade, while knowing definitively that a number of astounding, unforeseen events will unfold.

The capital markets are generally very skilled at making fools of people who make broad, sweeping predictions that turn out to be dead wrong. While acknowledging that some of our predictions will prove to be incorrect, we present our Ten Predictions for the 2020s:

- The dollar-centric international monetary system becomes a multi-polar monetary system.

The U.S. dollar share of foreign central bank holdings continue to decline, as the dollar is used less in international trade. Conversely, the Chinese Yuan, the Euro, the Japanese Yen, and gold will play an increasingly important role in foreign central bank holdings. With lower international demand for dollars, the U.S. dollar exchange rate declines, benefiting U.S. producers with increased export competitiveness while harming U.S. consumers with higher import prices. With dollar weakness, U.S. manufacturing resurges, inflation accelerates, and Federal debt levels eventually becomes more manageable.

– - Without reform, the Federal Reserve’s monetary role increases, and interest rates remain low.

With foreign central banks backing away from U.S. Treasuries and a ballooning budget deficit, the Federal Reserve becomes the last resort buyer of U.S. Treasuries in a significant and noticeable way. These Treasury purchases fund the government’s defense spending, entitlement obligations, and interest payments, while also capping interest rates on U.S. Treasuries at low levels. With interest rates capped by the Federal Reserve, U.S. fixed income investments generate rates of return that do not exceed the inflation rate.

– - A resurgent U.S. Department of Justice pursues antitrust actions against monopolistic corporations.

Several large, near-monopolistic technology companies face new regulations and/or are broken up as the U.S. government attempts to curtail their power and foster increased competition. As part of this breakup, many of the free or heavily discounted services provided by these companies dissipate. The U.S. government also places size limitations on commercial and investment banks, causing the largest banks to break up into smaller pieces.

– - The S&P 500 disappoints.

After one of the longest bull markets in history, the stock market disappoints in the 2020s. Weaker S&P 500 investment returns are driven by the following:- Stock valuations in the United States are sky-high at the beginning of the decade and come down to more reasonable levels by 2030. Accelerating inflation reduces the present value of companies’ future cash flows, resulting in a stock market P/E ratio at the end of the decade that is well lower than the start of the decade.

- Corporate share buybacks cease. Because buybacks had been the predominant buyer of stocks throughout the post-Financial Crisis period, the lack of buybacks has a considerable impact on demand for equities, negatively affecting share prices.

- Corporate profit margins, which began the decade at record high levels, decline over the next ten years due in large part to higher wages, increased import prices, and efforts taken by the Federal government to prosecute antitrust cases.

- To fund living expenses during retirement, aging baby boomers sell their housing, stock, and bond holdings at discounted prices to a smaller population of Generation Xers and Millennials.

–

- Value stocks meaningfully outperform growth stocks.

As investors start to pay attention to business fundamentals, earnings, and cash flows, investors rotate out of expensive tech companies and into relatively inexpensive value stocks. The cheapest part of the stock market at the beginning of the decade considerably outperforms the most expensive stocks in the stock market, similar to what transpired during the 2000s as the dot-com bubble ended.

– - International stocks outperform U.S. stocks, led by emerging market stocks.

As the dollar weakens, foreign stock markets as denominated in U.S. dollars outperform the U.S. market. In many of these international markets, cyclically-adjusted price/earnings (CAPE) ratios are currently undemanding, and particularly so in emerging markets, which means that the valuations of foreign stocks are likely to rise during the next ten years. Some of the big winners include now out-of-favor stock markets like China, Italy, Russia, Brazil, and South Korea, all of which trade at CAPE ratios well below that of the S&P 500.

– - Gold shines.

With 10-year bond yields below the rate of inflation, investors increasingly rely less on fixed income investments as a foundational store of value within investment portfolios. Conversely, with interest rates low and inflation accelerating, gold’s investment attractiveness improves, as gold becomes an essential part of many investors’ strategic asset allocations. At the same time, central banks continue to increase their purchases of gold as a neutral reserve asset to settle accounts with other countries. As a result of increased demand by central banks and private investors alike, the gold price more than triples by the end of the decade.

– - Blockchain-based cryptocurrencies like bitcoin become the biggest loser of the decade.

Digital currencies continue to grow, but bitcoin and other blockchain-based cryptocurrencies lose their luster. Private cryptocurrencies become one of the worst-performing asset classes of the decade as it becomes evident that cryptocurrencies will never be embraced by the international monetary system as alternative currencies. Concurrently, a group of central banks collaborates to issue and administer a new and revolutionary digital currency system, which allows for far greater transparency, efficiency, safety, reliability, and government control than the current non-digital currency system. This new digital currency system enables a myriad of new monetary tools that could not be applied today.

– - Underfunded public pension plans receive a Federal bailout.

With increasing liabilities and unreasonable assumed investment rates of returns, underfunded public pension plans create a financial crisis. Municipal bond markets freeze up, and social unrest grows as retired teachers, police officers, and firefighters across the country demand assistance from the Federal government. Congress bails out insolvent pension plans in return for structural reforms that prevent the problem from recurring. The pension bailout causes further weakness in the U.S. dollar exchange rate as foreign investors worry further about the weakening fiscal discipline of the United States.

– - The explosion in student debt forces dramatic changes in higher education.

As college unaffordability worsens further, scores of Tier Two and Tier Three private universities declare bankruptcy and liquidate. New startups that focus entirely on vocational training proliferate and take significant market share from traditional educational institutions. Responding to these changes, large companies in the United States stop insisting on a college degree as a hiring prerequisite for many white-collar jobs.

A decade is a long time, and we expect significant trends to develop that we are not even contemplating, nor for that matter, is anyone else contemplating. One thing we expect will not change is our approach towards investing. We will be looking for value, we will be wary of risk, and we will continue to invest our clients’ long-term capital commitments like we do our own capital, with prudence and discipline. We wish you and your families a happy, healthy, and prosperous decade, and we look forward to working hard on your behalf in the coming years with regards to your prosperity.

At the end of 2019, the former President of Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management, Ron Strauss, unexpectedly passed away at the age of 80. Ron played a larger-than-life role for those of us who were lucky enough to work with him. His role as mentor, partner, friend, and father figure was invaluable to all of us. He taught us by example: working hard, putting clients first, caring about the good of the firm’s associates, using ethics as a guide stone, and being committed to prudent, disciplined value investing. Ron positively influenced all of us at Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management; we will miss him terribly, and we appreciate the many notes of condolence that we have received during the past few weeks.

Farewell, our friend and mentor.

Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management

[1] To provide a sense of scale, 2018 U.S. GDP was only $20.5 trillion.

[2] Source: Deutsche Bank.

[3] Source: TechCrunch.

This commentary is prepared by Pekin Hardy Strauss, Inc. (dba Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management, “Pekin Hardy”) for informational purposes only and is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. The information contained herein is neither investment advice nor a legal opinion. The views expressed are those of the authors as of the date of publication of this report, and are subject to change at any time due to changes in market or economic conditions. Although information has been obtained from and is based upon sources Pekin Hardy believes to be reliable, we do not guarantee its accuracy. There are no assurances that any predicted results will actually occur. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. The S&P 500 Index includes a representative sample of 500 hundred companies in leading industries of the U.S. economy, focusing on the large-cap segment of the market. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is an unmanaged index representing the rate of the inflation of U.S. consumer prices as determined by the U.S. Department of Labor Statistics.