Photo by chungking

“The more troublous the times,

the worse does a laissez-faire system work.”

– John Maynard Keynes

National Liberal Club lecture (December 1923)

Although John Maynard Keynes, arguably the most famous economist in the history of the world, died more than 70 years ago, he likely would have something thought-provoking to say about the state of the economy if he were alive today. Coming of age during the early years of the 20th century, Keynes was trained as a classical economist; he learned that taxes should be low, regulatory interference should be minimal, and economic growth for trading nations could only be maximized under a regime of free trade. In his early years as an economist, Keynes considered anyone who opposed free trade as unfit to be an economist.

Although John Maynard Keynes, arguably the most famous economist in the history of the world, died more than 70 years ago, he likely would have something thought-provoking to say about the state of the economy if he were alive today. Coming of age during the early years of the 20th century, Keynes was trained as a classical economist; he learned that taxes should be low, regulatory interference should be minimal, and economic growth for trading nations could only be maximized under a regime of free trade. In his early years as an economist, Keynes considered anyone who opposed free trade as unfit to be an economist.

Keynes embraced classical economics and free trade until the British economy became mired in a severe recession during the years between World War I and World War II. As economic circumstances in Great Britain deteriorated, Keynes threw his free trade views out the window and chose to vigorously support Great Britain’s efforts to raise tariffs and devalue the sterling against the dollar. After the 30% sterling devaluation which occurred in September 1931, Great Britain’s economy started to grow again and gradually began to emerge from its own Great Depression.

Keynes believed that Great Britain’s economic ills and lack of industrial competitiveness were largely driven by the British sterling’s high fixed exchange rate relative to gold (at a time when the world monetary system was on the gold standard). Today, the world’s monetary system is no longer on a fixed gold standard; instead, the global monetary system relies on a fiat dollar standard. Nevertheless, we believe Keynes would diagnose current economic problems in the United States to be at least partly related to a currency in the U.S. dollar which, for reasons we will discuss, similarly has an exchange rate value which is simply too high for many U.S. producers to be competitive.

While acknowledging the importance of international trade for the long-term health of the global economy, we will not be making a principled argument for free trade in this letter, for two reasons. First, in an era where the price of stocks, interest rates, and currencies are managed by central banks, “free trade” simply cannot exist. Second, as a financial advisor, our job is not to describe what should be, but, rather, to understand what is (and what will likely be) and to position client investment portfolios accordingly.

Ushered into office by a constituency that has suffered from the demise of manufacturing jobs over the past several decades, the Trump administration has begun discussing a wide range of protectionist initiatives from increased tariffs to border adjustment taxes. However, none of these measures will materially improve the trade deficit as long as the dollar remains the world’s reserve currency and as long as foreign countries continue to generate large levels of excess savings that are invested in U.S. Treasuries.

In this letter, we explore the connection between the balance of payments and structural trade imbalances, some of the ways these structural imbalances might be corrected, and what the investment implications of a structural adjustment might be for the economy and for investors. We believe the United States and/or its trading partners are likely to eventually establish a new framework to govern money and trade that would result in more balanced trade relationships and a lower exchange rate for the dollar, and we are working to position client portfolios accordingly.

Balance of Payments

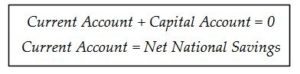

To better understand the dynamics of trade deficits, it is essential to understand an important accounting identity that comes from the following two balance of payments equations:[1]

States are positive; U.S. capital inflows finance the investments that the inadequate U.S. savings level cannot fund domestically. Conversely, if another country like China has a current account surplus, its net national savings rate is positive and China’s excess national savings will be invested in assets from other countries like the United States (e.g. U.S. Treasuries, Canadian real estate, African farmland). Adding up the accounts of all countries across the world, exports should match imports, capital inflows should match capital outflows, and world savings should net to zero.

Many people assume the best way to address a current account deficit, or trade deficit, is to erect trade barriers, and that is certainly one way to do it. However, other backdoor methods to improve a country’s balance of trade can also be used. For example, a country could choose to implement policies that increase the national savings rate or make decisions which force capital flows to reverse. A country could also choose to devalue its currency to improve the current account deficit. When U.S. policymakers accused China of “currency manipulation” several years ago, for example, it was because China had been buying U.S. Treasuries which created a capital account deficit and a corresponding trade surplus for China, while, at the same time, creating a capital account surplus and a corresponding trade deficit for the United States.

How Our Current Imbalances Developed

How Our Current Imbalances Developed

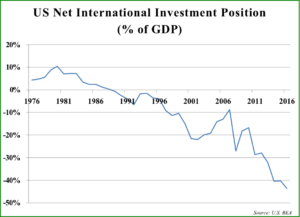

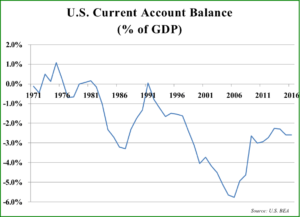

After Nixon closed the gold window in 1971, the fiat U.S. dollar without gold exchangeability essentially became the world’s reserve currency. Henceforth, trade imbalances, left unaddressed as foreign countries accumulated dollars and as the United States accumulated debt, have steadily worsened. The “exorbitant privilege” of issuing the world’s reserve currency has allowed (or forced) the United States to run a persistent trade deficit to offset the persistent capital inflows that necessarily occurred as the rest of the world bought dollars to conduct trade.

Given the openness of U.S. capital markets and the role of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, it logically follows that capital flows have driven trade flows rather than vice versa. According to Richard Koo, Chief Economist at Nomura Research Institute, 95% of currency trading transactions are capital (investment) related rather than trade related, and those capital transactions are the primary driver of U.S. trade deficits due to the balance of payments. Put differently, the United States has become the world’s consumer of foreign production in part because other countries have been accumulating U.S. financial assets. The end result is a persistent current account deficit and an ever-worsening international investment position as capital inflows continue to exceed capital outflows.

Given the openness of U.S. capital markets and the role of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, it logically follows that capital flows have driven trade flows rather than vice versa. According to Richard Koo, Chief Economist at Nomura Research Institute, 95% of currency trading transactions are capital (investment) related rather than trade related, and those capital transactions are the primary driver of U.S. trade deficits due to the balance of payments. Put differently, the United States has become the world’s consumer of foreign production in part because other countries have been accumulating U.S. financial assets. The end result is a persistent current account deficit and an ever-worsening international investment position as capital inflows continue to exceed capital outflows.

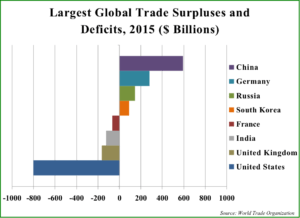

The greatest trade imbalance in the world today is the trade surplus of China on one side of the balance of payments ledger and the trade deficit of the United States on the other side of the balance of payments ledger (see chart above). According to Michael Pettis, professor of finance at Peking University in Beijing, China has systematically pursued a policy of holding down its share of national income that goes to households for decades to boost China’s savings rate and, relatedly, through the balance of payments, China’s trade surplus. Through balance of payments accounting, China’s high savings rate has resulted in persistently large trade surpluses and capital flows into other countries that are the highest in the world. China has exported its manufactured goods to the United States, while the United States has exported industrial jobs and U.S. Treasuries to China.

The greatest trade imbalance in the world today is the trade surplus of China on one side of the balance of payments ledger and the trade deficit of the United States on the other side of the balance of payments ledger (see chart above). According to Michael Pettis, professor of finance at Peking University in Beijing, China has systematically pursued a policy of holding down its share of national income that goes to households for decades to boost China’s savings rate and, relatedly, through the balance of payments, China’s trade surplus. Through balance of payments accounting, China’s high savings rate has resulted in persistently large trade surpluses and capital flows into other countries that are the highest in the world. China has exported its manufactured goods to the United States, while the United States has exported industrial jobs and U.S. Treasuries to China.

Due to the nature of the balance of payments, the United States cannot easily reduce its trade deficit without a corresponding adjustment with regards to China’s trade surplus. This adjustment, while perhaps necessary in the long-term, will be difficult due to the massive manufacturing capacity that has been created in China and the dependence that China’s regime has on keeping its populace employed by exporting products to other countries.

Correcting Trade Imbalances

In 1930, Keynes proposed that Great Britain take unilateral actions to pursue protectionism and devaluation to solve its economic problems. Without a comprehensive multilateral agreement gradually moving away from the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, it is likely that the United States, sooner or later, will pursue a similar unilateral path to currency devaluation as 1930s Great Britain.

U.S. policymakers are currently looking to improve the country’s trade deficit through a number of mechanisms, including bilateral trade agreements, unilateral tariffs, and tax reform (which could include a border adjustment tax). Bilateral trade agreements by themselves seem like an ineffective solution given that structural imbalances are global and not bilateral; moreover, any bilateral trade agreements would require approval of two-thirds of the Senate. Either a border adjustment tax or a value-added tax (VAT) would be easier for Congress to pass and would reduce the trade deficit; such taxes would reduce consumption as a percentage of GDP while forcing an increase in the national savings rate, thereby improving the U.S. trade balance.

Another potential strategy involves the Federal Reserve devaluing the exchange rate value of the dollar. This strategy may be an attractive option for the Trump administration.[2] Former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, in his famous 2002 speech about deflation where he earned the infamous moniker “Helicopter Ben,” described exchange rate policies as one of the monetary tools that the Federal Reserve could deploy to stimulate nominal GDP growth:

The Fed has the authority to buy foreign government debt… Potentially, this class of assets offers huge scope for Fed operations, as the quantity of foreign assets eligible for purchase by the Fed is several times the stock of U.S. government debt. I need to tread carefully here. Because the economy is a complex and interconnected system, Fed purchases of the liabilities of foreign governments have the potential to affect a number of financial markets, including the market for foreign exchange.

We believe that Keynes would approve of such an exchange rate adjustment to boost exports and domestic employment. Using a balance of payments lens, buying foreign government debt would result in a capital outflow for the United States, which would improve the U.S. current account deficit, all other things being held equal. It would also result in a lower exchange rate for the dollar and U.S. exports becoming priced far more competitively. Importantly, unlike a border adjustment tax or a new set of trade treaties, an exchange rate adjustment would not require Congressional approval; by mid-2018, the President will have had the opportunity to appoint at least four out of the seven voting positions on the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC). By lining the Federal Reserve Board of Governors with new appointees who support a weaker dollar, President Trump could provide exchange rate support to improve the competitiveness of U.S. producers.

Besides unilateral actions that the United States might take to improve its trade deficit, there is also a scenario whereby world leaders create a new multilateral set of trade and monetary agreements, resulting in the gradual replacement of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency with something else. Several reserve currency options could be used for settlement instead of the dollar; these options include the SDR (Special Drawing Rights), a super-national currency issued by the IMF, while another option might involve multiple regional reserve currencies including the dollar, the Euro, and the Yuan, each of which might be exchangeable into gold once again.

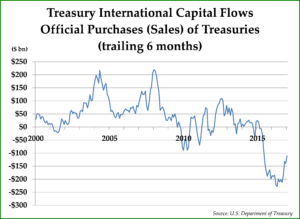

Indeed, there are reasons to believe that an important monetary transition may have already begun. In 2013, Yi Gang, a deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China, made a stunning admission when he said, “it’s no longer in China’s favor to accumulate foreign-exchange reserves [U.S. Treasuries].”[3] China has formed several agreements with trading partners, including Russia and Iran, whereby it settles trade in yuan rather than in dollars. Since then, China’s foreign official holdings of U.S. Treasuries have stopped increasing and have in fact been declining since 2014 (see chart on below), just one year after Yi Gang’s speech. And, due to China’s important role as a buyer of U.S. Treasuries, for the first time since 1971, foreign governments as a group have been selling rather than buying U.S. Treasuries over the past couple of years. If this trend continues, an important support for the value of the dollar will disappear, and an important impediment for rebalancing U.S. trade will also disappear.

Monetary Transition Implications

Our crystal ball on the exact path forward with regards to a rebalancing transition and on the timing of that path is just as cloudy as the next person’s crystal ball. However, we have been gradually preparing client investment portfolios for the monetary transition described in this letter for years. Below is a list of developments we are expecting could occur before the Trump administration ends:

- Increased volatility:

The trade and capital related imbalances that exist today have built up gradually over a 35-year period. It seems unlikely that the world will move from the currently imbalanced trade system to a more rebalanced trade system without elevated volatility and geopolitical instability along the way — particularly so given the indebted balance sheets of individuals, companies, and governments in the developed world. In worst case scenarios, economic volatility could result in geopolitical conflicts beyond that which has occurred during the last few years.

- Exchange rate adjustments:

Whether driven by tax policies, trade treaties, monetary policy, or a new multi-lateral trade agreement, a balanced world trade environment would result in reduced foreign demand for U.S. Treasuries and a lower exchange rate for the dollar. Countries with a trade surplus should experience currency appreciation, while countries with a trade deficit should experience currency depreciation. Accordingly, surplus country currencies and investments in real assets should perform better compared to dollar denominated investments.

- Less consumption and more savings:

With less foreign capital coming into the United States, the U.S. savings rate will have to increase and U.S. consumption would have to decrease as a share of U.S. GDP. Economic policies that attempt to limit U.S. consumption – such as a VAT tax – may help boost the national savings rate. In our view, increasing the national savings rate would be particularly challenging given the large wave of baby boomers who are retired or are soon entering retirement. This scenario does not bode well for companies with high exposure to U.S. consumer discretionary spending.

- Lower debt leverage:

Dollar devaluation will result in faster nominal growth, increased nominal GDP, and higher nominal incomes in the United States. While inflation generally reduces a country’s standard of living as the costs of imports increase, the silver lining is that the United States will service its fixed rate debt more easily as prices and incomes rise. At a national level, the Debt/GDP ratio will decline, and, at the household level, Debt/Income ratios will decline.

- More production and employment :

U.S. manufacturing and U.S. exporters should become more competitive if and when the dollar depreciates against other currencies.

These predictions are dependent on significant structural changes to global trade and capital flows that may or may not take place imminently. Global trade and capital flows have been highly imbalanced for the past 35 years, so it is certainly possible they could remain highly imbalanced for years to come. That said, the structural imbalances that today’s dollar-centric monetary system has created are becoming increasingly untenable, both economically and politically.

Thus, over the past several years, we have been gradually accumulating gold, real estate, and other hard assets that should at least retain their inflation-adjusted value if a dollar devaluation occurs. If and when the dollar declines in value, hard assets should retain their inflation-adjusted value and rise in dollar terms. Also, given the accumulation of gold by the central banks of China and Russia over the last ten years, we would not be surprised to see gold increase in importance again as a means of settling trade or capital imbalances between countries.

For similar reasons, we have been investing increasingly in non-U.S. dollar denominated equity and fixed income investments, including companies that derive a substantial percentage of their earnings in the currencies of surplus trade countries. Countries like South Korea, Taiwan, China, and Germany, all of which have significant trade surpluses, should experience currency appreciation versus the dollar when trade and currencies rebalance.

Finally, we are generally tilting client portfolios towards more defensive U.S. investments, and we have become increasingly selective with regards to companies with significant exposure to U.S. consumer discretionary spending. Instead, we are trying to identify attractively priced investments in U.S. companies whose revenues and earnings are likely to hold up in an environment of weak economic growth and in U.S. companies whose revenues and earnings should benefit from dollar depreciation.

*****

Before we close out this letter, we want to share the bittersweet news that Rick Singer, who was one of the original three founders of Pekin Singer Strauss Asset Management, has decided to retire after a 45 year career. Rick has been working part-time over the past several years, splitting his time between Chicago and Florida, but he now wants to make a full-time move to the Sunshine State. Over the years, Rick has been a friend, a mentor, and a constant source of wisdom for all of us who have had the privilege to work with him. As scintillating as our investment meetings may be, they are no longer a match for a good doubles tennis game; we wish Rick many years of health and energy in his retirement allowing for much enjoyment and satisfaction, whether it be playing doubles tennis or spending time with grandchildren.

It is always a great honor for us to be able to share our thoughts with you and to have you as a valued client. With increased economic uncertainty and, increasingly, political uncertainty, we are doing our best to position your investment portfolio to navigate through these uncharted waters.

Sincerely,

Pekin Singer Strauss Asset Management

This commentary is prepared by Pekin Singer Strauss Asset Management (“Pekin Singer”) for informational purposes only and is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. The information contained herein is neither investment advice nor a legal opinion. The views expressed are those of the authors as of the date of publication of this report, and are subject to change at any time due to changes in market or economic conditions. Although information has been obtained from and is based upon sources Pekin Singer believes to be reliable, we do not guarantee its accuracy. There are no assurances that any predicted results will actually occur. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

[1]The “Current Account” is an economic term that equals exports minus imports with some minor adjustments related to net investment income and net transfers. In this letter, we will be using terms such as “Trade Deficit” and “Current Account Deficit” interchangeably, because exports minus imports is the primary driver of the Current Account. The “Capital Account” is equal to U.S. purchases of foreign assets minus foreign purchases of U.S. assets, including foreign official (central bank) purchases of U.S. assets such as U.S. Treasuries. “Net National Savings” is equal to National Savings minus National Investments. When the Net National Savings figure is negative, foreigners invest their capital in U.S. assets to fill the gap between Net National Savings and Net National Investments.

[2] Source: Luke Gromen, Forest for the Trees.

[3] Source: Bloomberg, November 2013 and TTMYGH, December 2016.