Photo by freshidea

“In 1930, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, in an effort to alleviate the effects of the… Anyone? Anyone? …the Great Depression, passed the… Anyone? Anyone? The tariff bill? The Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act [sic]? Which, anyone? Raised or lowered? …Raised tariffs, in an effort to collect more revenue for the federal government. Did it work? Anyone? Anyone know the effects? It did not work, and the United States sank deeper into the Great Depression.”

— Economics Teacher, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

History often repeats itself; when the economy is persistently weak, populism and trade protectionism tend to rise. In light of President Trump’s recent tariff threats, financial news articles are citing the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 with increasing frequency. Signed into law by President Hoover, Smoot-Hawley raised tariffs on 890 products, increasing the average industrial tariff from 37% to 48%. While U.S. industrial workers cheer on new tariff proposals, free traders sternly warn that Trump is on the verge of making a Smoot-Hawley like mistake by starting a global trade war that could throw the world into a global depression.

Are these worries well-founded? Is Ferris’s teacher correct? Should we be selling our stocks to avoid a repeat of the ~90% stock market downturn that occurred between 1929 and 1933? Or are worries about repeating the mistake of Smoot-Hawley just a tempest in a teapot?

Based on the data, it is doubtful that Smoot-Hawley played a primary role in causing the Great Depression. Also, we doubt that the comparison between today and 1930 is appropriate, because persistent trade deficits were not a significant problem at that time. We would suggest that the primary investment risk of a trade war today is related to the potential impact on the capital flows from foreign countries which have supported the U.S. dollar over the last several decades. Thus, a trade war represents incremental risk to capital flows and the strength of the dollar.

Trade Tariffs, Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression

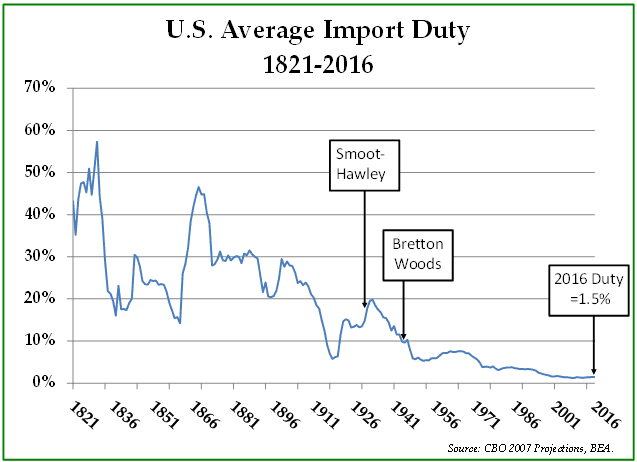

Since the industrial revolution began, the world has experienced great periods of prosperity even in the face of significant trade barriers. As demonstrated in the chart on the next page, the U.S. tariff rate averaged 10%+ between the 1830s and the 1940s, a period in which the United States grew enormously, as it evolved from an agrarian country into the world’s industrial powerhouse.

A year before Smoot-Hawley was signed into law, the stock market crashed on September 4th, 1929, with the worst performing sector being utility companies. Utility companies were heavily indebted, but their revenues and profits were largely unaffected by global trade. In other words, the possibility of a future trade war did not cause the crash. Prior to the 1929 crash, the Federal Reserve had tightened the availability of credit in order to temper the strong stock market, and monetary policy remained restrictive even after the crash. At that time, central banks were unwilling or unable to pursue countercyclical lending to stimulate demand. Subsequently, during the early 1930s, a series of banking crises took place in the United States and Europe which likely turned what should have been a garden variety recession into the Great Depression.

As the Depression deepened, world trade suffered due to inadequate global demand. However, inadequate trade was most likely the result rather than the cause of inadequate demand. While the Smoot-Hawley Act most likely worsened an already-bad situation, circumstances suggest that its economic impact was somewhat muted. Prior to the passage of Smoot-Hawley, European countries were already erecting trade barriers in response to their weakened economies. Importantly, Smoot-Hawley applied tariffs to roughly one-third of U.S. imports, representing just 1.3% of U.S. GDP. Furthermore, the tariff rate was already quite high prior to the Smoot-Hawley Act, with Smoot-Hawley increasing the average duty from 13.48% in 1929 to 17.75% by 1931.

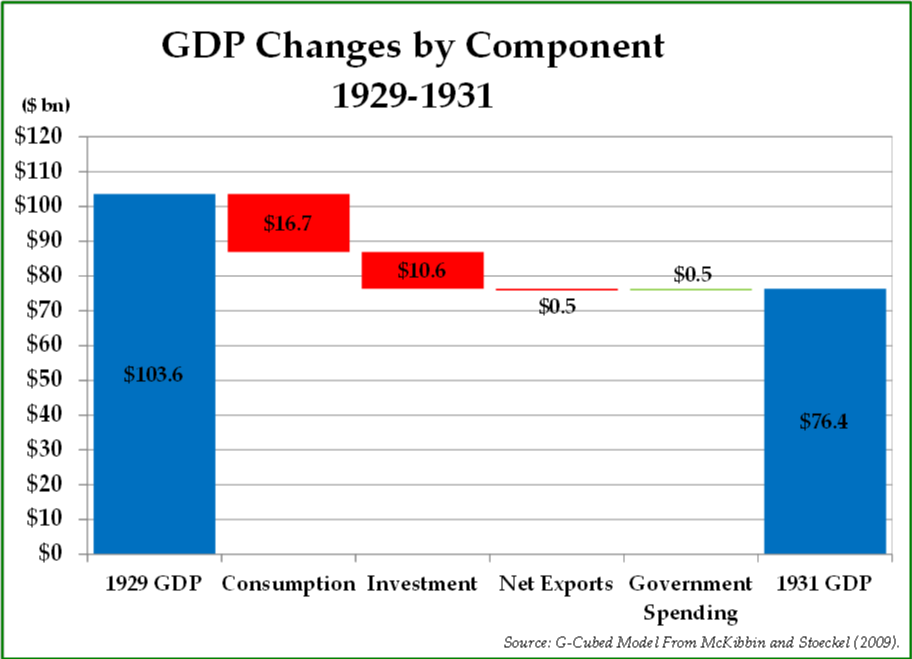

Perhaps more importantly, exports plus imports represented less than 10% of U.S. GDP in 1929; international trade was simply not as prevalent as it is in the present era. As such, the $470mm decline in net exports that occurred between 1929 and 1931 represented only 0.5% of U.S. GDP in 1929. Relative to the stunning 26.6% decline in U.S. GDP that occurred between 1929 and 1931, a 0.5% GDP detraction from net exports seems relatively minor when taken into context.

From Trade Surplus in 1930 to Trade Deficit in 2018

Just as Smoot-Hawley was a predictable political response to the decline in worldwide aggregate demand that began in 1929, the 2016 election of a trade protectionist as President of the United States was, in retrospect, a reflexive political response to the loss of the U.S. industrial manufacturing jobs over the past twenty years.

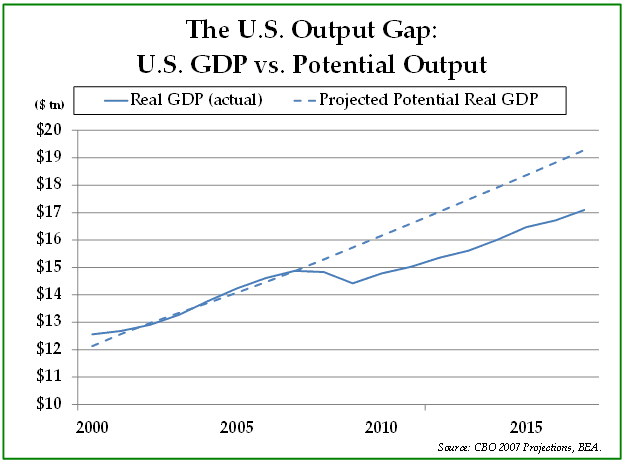

The chart below shows that the recovery of GDP since the Financial Crisis and the continuing output gap has been disappointing. The large and persistent output gap, representing the difference between actual GDP and the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) estimate of the maximum sustainable output of the economy, suggests that something permanent has impaired the U.S. economy. The continued disappointment in GDP growth, combined with a persistent trade deficit and increasing economic inequality, represent structural economic and social problems with no easy solution in sight.

Comparing the current era and 1930 with respect to global trade, three key differences stand out:

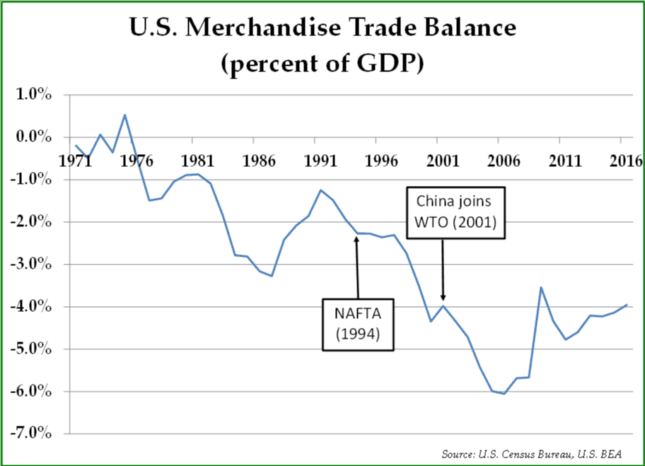

- In 1929, the United States was a surplus economy, with net exports of goods and services exceeding net imports, whereas today the United States runs a large trade deficit.

- Trade was largely balanced in 1929 with the U.S. trade surplus representing less than 1% of GDP, whereas in 2016 the U.S. merchandise trade deficit represented 4% of GDP.

- Trade is far more important today to the global economy, so the stakes are somewhat higher for all parties heavily involved in global trade.

Trade barriers make imports more expensive for consumers, thus suppressing aggregate demand. Because of its effect on demand, protectionism has a negative impact on economic activity for all parties involved. That said, in a trade war, trade surplus countries, such as China, are generally hurt more than trade deficit countries because the GDP of a surplus trade country is enhanced by its net exports to other countries. Similarly, trade deficit countries, such as the United States, suffer relatively less in a trade war because their net imports detract from GDP.

Given this dynamic, in retrospect, it seems odd that the United States passed a protectionist law like Smoot-Hawley in 1930. As a trade surplus country, the United States clearly stood to lose more than it had to gain from lower levels of world trade because, in 1929, the United States exported more goods and services than it imported. Indeed, when global demand declined as a result of the 1929 crash and subsequent banking crisis, every country suffered, but, as the world’s leading exporter, the United States economy suffered relatively more.

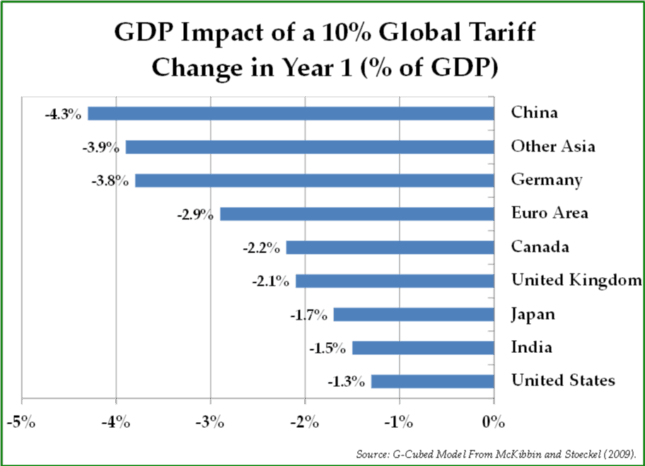

Today, in contrast, the United States is in a different situation. In this case, China’s GDP growth would suffer more than U.S. GDP growth because China has a large trade surplus while the United States has a large trade deficit. Two Australian economists, Warwick McKibbin and Andy Stoeckel, have modeled the impact of a 10% global tariff on GDP for each country, and they came to the conclusion that U.S. GDP would decline by an estimated 1.3%, while China’s GDP would decline by an estimated 4.3%, or more than triple the U.S. decline.

In other words, there are no winners in trade wars, but some countries lose more than others. The United States, with its large and highly diverse economy, should muddle through a global trade war comparatively better than export-driven economies such as China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and Germany, in our view. These surplus countries simply do not have the domestic demand to replace the export-related demand coming from the United States.

The Demise of Bretton Woods

The United States can choose an America First trade policy with balanced trade and balanced capital flows, or the United States can choose to maintain trade deficits and import capital to fund its national savings deficit. However, the United States cannot pursue a balanced trade deficit and also import capital to fund its increasing level of borrowing; after all, the balance of payments must – by definition – balance. Furthermore, if the United States ceases running a trade deficit, it cannot also provide the world with dollars with which to conduct trade.

Nobel-prize laureate in economics and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman raised this issue in 2013 when he suggested that U.S. protectionist policies would “break up the whole world trading system we’ve spent almost 80 years building.” That world trading system includes supra-national institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization (WTO), which support the growth of global trade and global capital flows. Created in Bretton Woods, NH in 1945, the post-war world trading system involved foreign countries holding U.S. dollars as a reserve asset and using U.S. dollars to conduct global trade. Seemingly validating Dr. Krugman’s point, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer recently discussed the Trump administration’s willingness, if necessary, to dispose of those institutions that have facilitated global trade since World War II for the purpose of reducing the U.S. trade deficit with China:

The sheer scale of their [China’s] coordinated efforts to develop their economy, to subsidize, to create national champions, to force technology transfer, and to distort markets in China and throughout the world is a threat to the world trading system that is unprecedented. Unfortunately, the World Trade Organization is not equipped to deal with this problem. The WTO and its predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, were not designed to successfully manage mercantilism on this scale. We must find other ways to defend our companies, workers, farmers, and indeed our economic system. We must find new ways to ensure that a market based economy prevails.

These supra-national institutions were created and supported for many years under U.S. leadership, so it is hard to imagine these institutions surviving an era where the United States is no longer willing to work through them to resolve trade disputes. Supporting Lighthizer’s views, in January 2018, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross participated in a panel at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland and agreed that it is finally time to break up the world trading system that was built in the aftermath of World War II:

Let me give you my version of post-World War II history. It was deliberate U.S. policy to help Europe and Asia recover from the ravages of the war…It was good policy globally and, until the 1970s, we had trade surpluses every single year, so it was an affordable policy decision (for the U.S. to reduce trade barriers). One of the ways they went wrong was not time limiting it…concessions that were totally appropriate to Europe or China or Japan in 1945 are singularly inappropriate as we sit here this year (2018). Now we’re left with the cumulative effect of it, and we are trying to deal with it in a very short time period.

With the support of global institutions like the WTO, for the past several decades the largest U.S. export has been U.S. Treasuries, and those U.S. Treasuries have been purchased and held by export-driven economies like China, Japan, and South Korea. In December, 2001, China was finally admitted into the WTO, and the People’s Bank of China went on a dollar buying spree immediately thereafter which continued up until 2013. China’s aggressive investments in U.S. Treasuries at a fixed exchange rate suppressed the exchange traded valued of the Yuan, but it also provided structural support for the dollar.

Of course, no trading system lasts forever, and the current trading system has its flaws. However, if the Trump administration follows through on its rhetoric to, in Dr. Krugman’s words, “break up the whole world trading system we’ve spent almost 80 years building,” without working with other countries to put a thoughtful new system in its place, the economic, geopolitical, and financial risks are significant and of an entirely different character than the risks represented by Smoot-Hawley.

Investment Implications

Based on the economic evidence, we would suggest that the passage of Smoot-Hawley was not a positive development for the ailing U.S. economy in 1930, but it was not the primary cause of the Great Depression either. In this view, we concur with Dr. Krugman, who said in 2010, “I don’t think the Smoot-Hawley tariff was a good thing…but did Smoot-Hawley and other trade restrictions cause the Depression? No.” In our view, comparing the passage of Smoot-Hawley to President Trump’s tariff threats is also not particularly useful because the U.S. role in global trade has evolved considerably since 1930.

To be sure, there are plenty of reasons to worry about the U.S. stock market and the global economy having nothing to do with trade:

- The U.S. stock market has been on a nine-year tear, which is a relatively long bull market.

- The overall valuation of U.S. stocks is high.

- The Federal Reserve is hiking interest rates, slowing down the economy and creating financial stress for highly indebted corporate and household borrowers.

- According to the Congressional Budget Office, the U.S. fiscal situation, already poor and deteriorating, is poised to worsen considerably as a result of the Trump tax reforms.

- Geopolitical risks remain at elevated levels.

Thus far, only trade saber-rattling has occurred; a true trade war has not yet commenced. While the risk of a trade war has increased, we think that it is more likely than not that an amicable resolution will be reached. Unfortunately, political outcomes such as a pending trade war are difficult to forecast.

That being said, any trade war that may develop would have inflationary consequences. With lower capital inflows, the dollar would decline in value, making U.S. imports more expensive. Conversely, U.S. exports would, in theory, increase with a lower value to the dollar. The risk then, of balancing trade, whether amicably determined or not, is that the purchasing power of dollar-denominated fixed income investments would decline, while the pricing power U.S. consumer discretionary companies would dissipate.

We expect that any acceleration in inflation due to a trade war would be generally detrimental to the prices of both stocks and bonds due to a likely increase Mr. Market will want to earn from the interest rates on his Treasury bonds. However, at a certain point, we also would expect the Federal Reserve to intervene, keeping interest rates low while allowing the dollar to decline versus other currencies. Our biggest worry about a trade war is that the real purchasing power of fixed income investments could become impaired. For that reason, we are keeping our fixed income durations short.

Having said that, other investments may benefit from a weaker dollar, such as:

- Reasonably valued equities, and especially the equities of multi-national companies and foreign companies whose revenues are generated in non-dollar currencies.

- Foreign currency bonds, and especially foreign currency bonds of countries who currently run a large trade surplus.

- Companies that operate in the agricultural sector, because a weaker dollar will enhance the competitiveness of the U.S. agricultural sector.

- Precious metals.

- U.S. exporters who should enjoy enhanced competitiveness with a weaker dollar.

Beyond international trade, we also worry about excessively high debt levels across the consumer, corporate, and government sector. In our view, high debt levels represent a greater risk to the stock market than a trade war, and particularly so as the Federal Reserve continues to raise short-term interest rates. If there is a significant stock market correction this year, we believe that it will likely be driven by a slowdown in credit expansion and related economic activity as consumers, corporations, and investors react to higher interest rates.

Based on the increase in recent trade rhetoric, we are not making material changes to client portfolios. We have already been positioning for a weaker dollar by increasing our purchases of foreign stocks, foreign bonds, and precious metals. The best remedy for an uncertain environment is to diversify across a broad range of asset classes, including other currencies and assets that could increase in price in an inflationary environment.

As usual, our view is more focused on the long-term investment horizon, which goes beyond just the next six months. With that view, recent volatility in the stock market is also beginning to present us with more attractive investment opportunities. If the volatility continues and the stock market corrects further, we expect our level of investment activity on behalf of our clients to increase.

*****

We appreciate having the opportunity to work with you. It is deeply meaningful for us to invest on your behalf, and to help you make decisions that enable you to better reach your financial goals.

Sincerely,

Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management

This commentary is prepared by Pekin Hardy Strauss, Inc. (“Pekin Hardy”) for informational purposes only. Pekin Hardy Strauss, Inc. does business as Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management, encompassing financial planning and separate account management services for individuals and families, and as Appleseed Capital, the firm’s institutionally-focused arm. The information contained herein is neither investment advice nor a legal opinion. The views expressed are those of the authors as of the date of publication of this report, and are subject to change at any time due to changes in market or economic conditions. Although information has been obtained from and is based upon sources Pekin Hardy believes to be reliable, we do not guarantee its accuracy. There are no assurances that any predicted results will actually occur. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.