“When you remember we are all mad, the mysteries disappear and life stands explained.”

─ Mark Twain

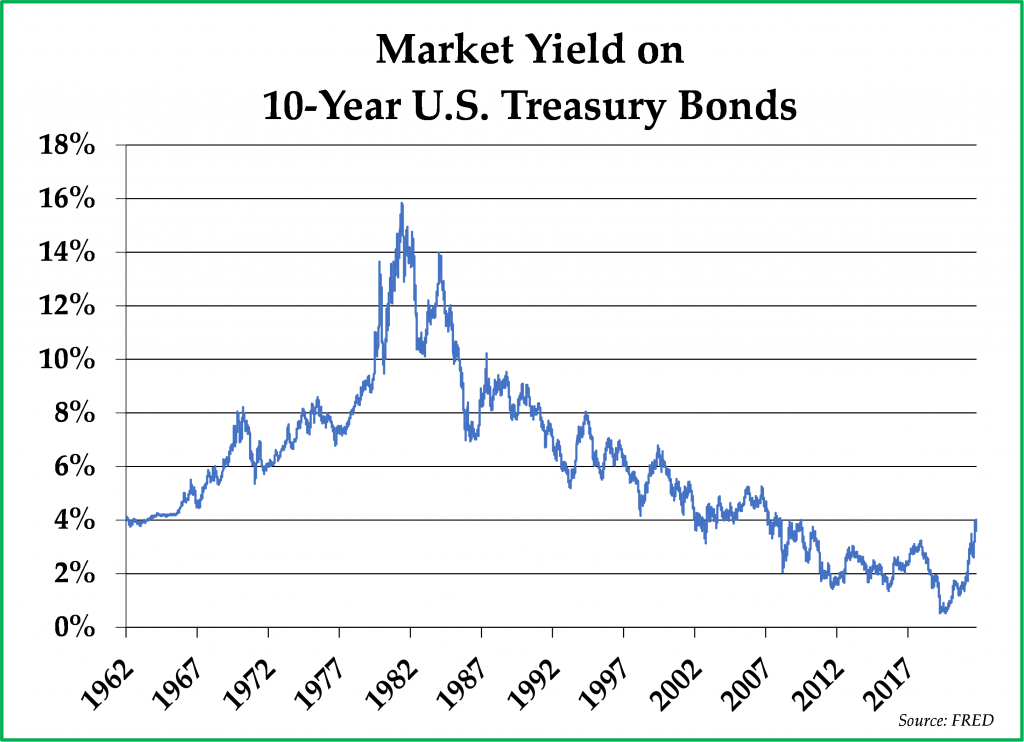

In past letters, we have addressed the craziness of the current investment era multiple times. In August 2020, 10-year Treasury bond yields reached an all-time low of 0.5% while $17 trillion dollars of sovereign bonds in Europe and Japan were paying negative yields to investors. Using the word “madness” to describe the interest rate environment in 2020 would have been entirely appropriate; the interest rate trough reached that month likely represented the lowest interest rates in 5,000 years of monetary history.

Looking at interest rates today, quite a different picture emerges. The Federal Reserve has been tightening monetary policy by hiking short-term interest rates aggressively to alleviate inflationary pressures in the economy. At the same time, the Federal Reserve has also been boosting long-term interest rates this year by ceasing its Quantitative Easing program whereby the Federal Reserve was previously purchasing long-term Treasury bonds to cap interest rates. As a result of these tightening measures, Treasury bond yields have been normalizing quickly. The 2-year Treasury bond yield has increased to 4.5%, while the 10-year Treasury bond yield has increased to 4%. These interest rates stand well below the current inflation rate, but quite a bit more than the 0.5% interest rate that 10-year Treasury bonds were paying in August 2020. Moreover, without a reversal in policy, it appears that interest rates have further room to rise.

Outside the United States, interest rates generally have been increasing this year, for many of the same reasons, and global financial markets have reacted accordingly. The global stock market is now in a bear market and, remarkably, the U.S. Treasury bond market is in the midst of its deepest correction of the past 100 years. Global economic growth has slowed to recessionary (or near recessionary) levels as consumers pull back on purchases of housing and automobiles while companies have placed restraints on their capital expenditures. Just as 2008 and 2020 have become important years of market history, so too will 2022.

Equity and bond markets aside, the currency markets have also experienced historically extreme exchange rate gyrations thus far in 2022. Several emerging market countries are in the midst of full-blown currency crises. For example, the Sri Lankan Rupee is down 78%, the Argentinian Peso is down 30%, and the Turkish Lisa is down 28% through 9/30/22. While these currency moves are extreme, they have happened before in emerging market countries. What makes this time different is that they are also happening in developed economies. From the beginning of the year through 9/30/22, the Japanese Yen is down 25%, the United Kingdom Pound Sterling is down 21%, and the Euro has declined 16%. All of these currencies, emerging and developed, have weakened considerably against the US Dollar.

Some analysts have called the dollar’s remarkable strength this year a “wrecking ball.” Indeed, a strong dollar is not a good thing for financial markets (just look at declines in the stock and bond markets) or for the global economy (currently heading into a global recession). Arresting the depreciation of currencies around the world is necessary to alleviate extreme inflationary pressures outside the United States and allow real growth to recover from the currently dismal levels. The root causes of these extreme currency movements vary by country, but the primary drivers include interest rate differentials, a worldwide energy crisis exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, and margin calls on dollar-denominated debts.

- Interest Rate Differentials

Interest rate differentials can cause significant movements in exchange rates. In a world with free capital flows, if Country A pays an interest rate of 5% and Country B pays an interest rate of 2%, all things being equal, investors are going to sell their bonds in Country B and buy the bonds of Country A to earn more interest, thereby causing Country B’s currency to depreciate and Country A’s currency to appreciate relative to each other. As a result, when the United States raises interest rates aggressively, it causes the dollar to appreciate unless other countries follow suit with aggressive interest hikes of their own.

- Energy Crisis

As the price of energy increases, it can have a significant effect on a country’s trade balance and currency exchange rate. In general, when oil prices strengthen, so too do the currencies of energy exporters, whose exports are increasing, while the currencies of energy importers tend to depreciate because of increasing import values. For example, the Russian Ruble has been the strongest currency in the world during the first nine months of 2022, appreciating 19.1% versus the U.S. dollar, while the Sri Lanka rupee has lost almost 80% of its value versus the U.S. dollar. Russia is a significant energy exporter, while Sri Lankan experienced a currency crisis when it ran out of dollars to import shiploads of fuel, cooking gas, and food, all of which increased in price considerably this year.

- Dollar-Denominated Debt

Because the dollar is the world’s reserve currency, many foreign countries issue bonds that are denominated in U.S. dollars. Two extreme examples are Argentina, where more than 50% of its debts are denominated in dollars, and Columbia, where more than 30% of its debts are denominated in dollars. When the dollar rises, countries that owe debts in dollars are forced to spend local currency to buy dollars to pay back their debts. The Argentinian Peso and the Colombian Peso have depreciated by 30% and 12% versus the dollar, respectively, during the first nine months of 2022.

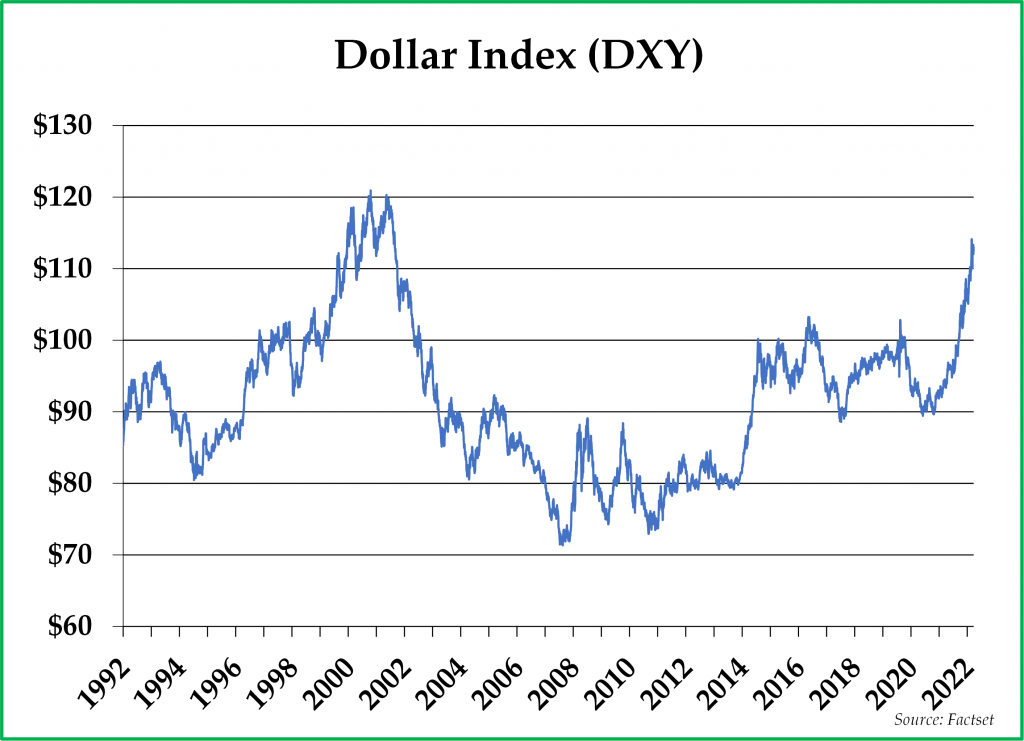

The DXY index, a measure of the dollar exchange rate against other developed market currencies, has soared by 16.8% year-to-date, reaching a level not seen since 2002. The narrative behind this remarkable dollar strength is that the U.S. dollar, while far from perfect, is the “cleanest dirty shirt” in a drawer full of even dirtier shirts. Put differently, the dollar does not deserve to be strong, but it does deserve to be stronger than other currencies which are even worse. There is some truth to this narrative, but we want to explore why the relative relationships have changed to such a great extent this year.

- The Euro: -16.0% vs. the U.S. Dollar YTD

Germany, the industrial powerhouse of Europe, had previously maintained its competitiveness as a goods exporter due in part to its ability to obtain cheap energy from Russia. In 2021, Russia accounted for 55% of Germany’s natural gas imports. In 2022, Russian natural gas exports to Germany have declined precipitously due to mechanical pipeline problems, economic sanctions, and, more recently, the sabotage of two underwater gas pipelines. To replace this previously cheap source of energy, Germany has been purchasing liquified natural gas (LNG) from other countries at much higher prices, turning on its coal plants, and pushing off the closure of several nuclear reactors. Due to a greatly increased cost of energy, German manufacturing plants are shutting down and/or declaring bankruptcy. The Euro area is now generating a trade deficit rather than a trade surplus for the first time in many years due to the sharp rise in the cost of imported energy and the reduced competitiveness of German exports.The Euro’s weakness is also attributable to low-interest rates. Interest rates in the Euro area have increased this year, but they are currently still 1% to 2% lower than interest rates in the United States. The Euro area cannot allow interest rates to rise too much because of the severe indebtedness of countries in southern Europe such as Italy, Spain, Greece, and Portugal. As a result, the European Central Bank (ECB) continues to buy government bonds to keep interest rates low, despite an environment of generationally high inflation rates.

- The Yen: -25.7% vs. the U.S. Dollar YTD

Japan is not as dependent on Russian natural gas as the Euro area. As LNG prices have risen, Japan has decided to accelerate the resumption of operations at the nuclear plants that were shut down because of the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami that subsequently destroyed the Fukushima nuclear plant. Japan depends on energy imports like Europe, but it is not yet experiencing an energy crisis to the extent that Europe is experiencing one.Nevertheless, the yen has also been depreciating significantly relative to the dollar due primarily to interest rate differentials. In Japan, deflation has been a problem for many years, and it appears that the Bank of Japan, seemingly unconcerned about inflation, is purposefully trying to engineer a weaker yen. The Bank of Japan is doing this by printing money to purchase Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs), thereby diluting the currency while keeping interest rates as low as possible. As a result, short-term interest rates remain negative in Japan and the 10-year JGB pays an interest rate yield of just 0.25%. The dollar, with much more attractive interest rates for investors, has been appreciating naturally versus the yen.Based on statements made by Bank of Japan Governor Kuroda, he perceives yen weakness to be a positive in that Japanese exports should become more competitive going forward. As trade relations between China and the United States deteriorate, Japan is trying to position itself as a viable replacement for China as a goods exporter, and its currency weakness is therefore part of a larger strategy to do exactly that.

- The British Pound: -21.3% vs. the U.S. Dollar YTD

Like Japan, the United Kingdom is a populous island nation, except without a meaningful export industry. The United Kingdom has run a trade deficit and a budget deficit for many years, both of which have been financed with capital inflows from countries like China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia whose investors have been purchasing London real estate. Like Europe, the United Kingdom has a significant energy deficit, and it has been trying to subsidize the energy costs of households and businesses with additional budget spending. Unlike both Japan and the Euro area, interest rates on U.K. government bonds are comparable to interest rates in the United States.The British Pound has depreciated versus the dollar for multiple reasons. First, the U.K. has been confiscating the assets of Russian billionaires, which is disconcerting for Russian investors and for rich investors from other countries that might not be 100% aligned with U.K. foreign policy. Second, the U.K. recently proposed an aggressive fiscal plan with no clear idea of how its deficits will be financed. Third, in recent weeks, the Bank of England has resumed printing money to cap interest rates to keep its pension plans solvent after they speculated incorrectly on the direction of interest rates. Finally, the U.K. has almost no foreign currency reserves with which it might defend its currency from depreciating.

In summary, the overall picture for currencies of the developed world is quite a gloomy one at the present moment, and the U.S. dollar has been appreciating because it is indeed in somewhat better shape on a relative basis. After all, the U.S. dollar still enjoys reserve currency status, and the United States can also supply most of its own food and energy needs. These benefits have not prevented the dollar from depreciating against energy and food prices this year, but it has prevented the dollar from depreciating against most foreign currencies. These advantages are longstanding advantages, but they have become much more important this year.

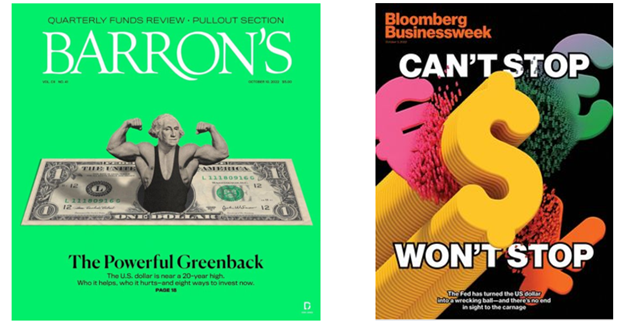

If the Federal Reserve continues to hike interest rates and the dollar continues to appreciate, most financial assets will continue to decline in price. This year, cash has beaten almost every asset class around the world. More and more investors are betting that the dollar’s strength will continue, extrapolating the current trend far into the future. Popular business magazine covers, which have historically proven to be a wonderful contrarian signal, suggest to us that the current bull market in the dollar might be closer to the end than the beginning.

This leads to the question of what might cause the dollar to stop appreciating versus other currencies. As always, we have no crystal ball with which to predict the future, but we would be looking for one or more of the following to happen in order for the dollar to depreciate against other currencies:

-

- The Federal Reserve ends its Quantitative Tightening (QT) program and begins a new round of money-printing to cap interest rates to allow the U.S. Treasury market to function more properly.

- Europe, Japan, and/or Great Britain develop a separate peace agreement with Russia that involves purchasing energy from Russia in local currencies.

- The Federal Reserve announces that it will pause hiking interest rates in response to softening employment data, a lower oil price, or a stock market decline deep enough to reduce wage inflation.

- The United States meets with other developed countries and agrees upon a currency accord that allows for the dollar to depreciate.

We would suggest that a reversal is likely a matter of weeks and months from now rather than years. The strength of the dollar is driven by quickly rising interest rates on U.S. Treasuries, which now exceeds 4%. Last year, the US Government paid approximately $400 billion in interest costs on its debt. If interest rates stay at current levels, then given rising Federal Debt levels, projected annual interest costs could easily exceed $1 trillion. The combination of a stronger dollar, rising interest rates, and an energy crisis are pushing the world into a recession which will soon put enormous pressure on the U.S. budget deficit as tax receipts historically decline during a recession. Due to the excessive indebtedness of the U.S. government, declining tax revenues combined with 4% interest rates would be an untenable situation which the U.S. government could not tolerate for very long.

When an eventual pivot happens, we believe that it will be an excellent time to own precious metals such as gold and silver, energy, commodity producers, and emerging market stocks. Until that time, we are staying somewhat defensive, with a larger-than-normal position in cash and short-term Treasury bonds.

*****

We are grateful, as always, for your entrusting us to manage your assets through challenging market environments such as the current one.

Sincerely,

Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management

This commentary is prepared by Pekin Hardy Strauss, Inc. (dba Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management, “Pekin Hardy”) for informational purposes only and is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. The information contained herein is neither investment advice nor a legal opinion. The views expressed are those of the authors as of the date of publication of this report, and are subject to change at any time due to changes in market or economic conditions. Although information has been obtained from and is based upon sources Pekin Hardy believes to be reliable, we do not guarantee its accuracy. There are no assurances that any predicted results will actually occur. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.