“The old world is dying,

and the new world struggles to be born:

now is the time of monsters.”

─ Antonio Gramsci, Italian Philosopher and Politician

During a different period of profound upheaval, Antonio Gramsci wasn’t talking about markets a century ago, but his sentiment applies rather aptly to today’s markets. Every so often, the world undergoes a major economic transition. From our vantage point, it appears that another transition has commenced.

The financial and geopolitical system that’s been in place since World War II — built around U.S. dollar dominance, open trade, and relatively stable global institutions — stands at the edge of a massive transformation. After eight decades of American military, economic, and financial hegemony, the current system is being replaced by something that looks more fragmented, more regional, and, on at least an interim basis, more inflationary.

Unquestionably, tariffs are rising. Free trade is declining, while managed trade is growing. Foreign capital has become increasingly unwelcome in the United States and is starting to return home, with less of it flowing into U.S. Treasuries. Gold is gaining ground as a reserve asset in substitution for U.S. Treasuries. At the same time, the United States is facing painful fiscal constraints and seems to be stepping back from its role as the world’s policeman. None of these developments are temporary or tied to any one political administration. For better or for worse, they reflect deeper seismic changes — an old system that’s collapsing, and a new one that is rising in its place. In this letter, we lay out how we see these structural changes unfolding and what they might mean for our clients and the capital markets. Our focus hinges on trying to navigate this new environment successfully through the current upheaval.

- Tariffs

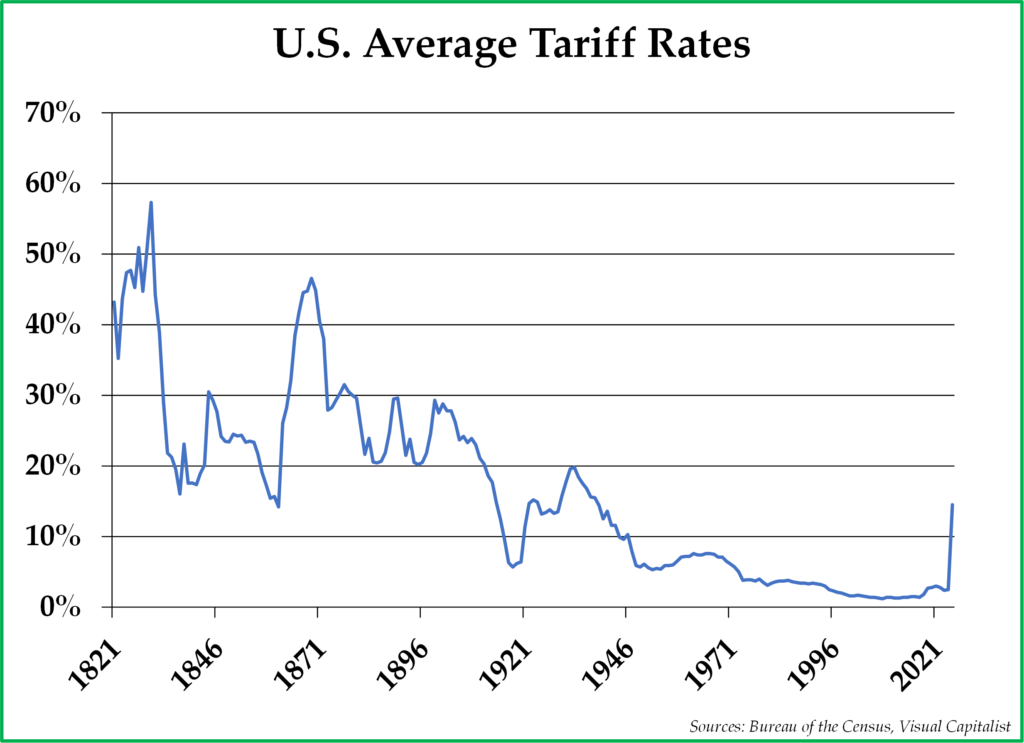

After decades of running massive trade deficits and shifting production overseas, the free trade era, at least with respect to the United States, is ending. The Trump Administration proposed raising tariffs broadly on April 2nd — starting at 10% and reaching as high as 154% in China’s case — to protect key industries and reduce reliance on adversarial countries. Notably, these tariff rates went well beyond Wall Street’s most pessimistic forecasts and will bring the average tariff above 20%, reaching the highest tariff rate since the 1930s. These tariff announcements triggered a quick decline in the stock market in the following days. In our view, the resulting trade war is unlikely to be short-lived; it’s part of a broader shift toward industrial policy, onshoring, and a trade framework built more around bilateral or regional agreements. President Trump’s goals are straightforward: bring more production home, reduce imports, boost exports, and raise new tax revenue. We shall see whether he is successful in accomplishing these goals; regardless, as we write this letter, the stock market dipped into bear market territory a week ago.

Of course, there are obvious trade-offs to Trump’s tariff goals. Less efficient supply chains usually mean higher costs, which will translate into inflationary prices for consumers and producers. Companies that depend heavily on foreign imports will likely feel margin pressure. On the other hand, businesses tied to domestic manufacturing, infrastructure, and energy may benefit. The White House claims that the additional revenue raised from tariffs could help reduce the Federal deficit and allow for middle-class tax relief. For investors, the shift toward higher tariff rates reinforces the importance of owning businesses with pricing power, strong production operations, and the flexibility to adapt to a more inward-looking economy.

- Capital Flight

While there’s a lot of warranted attention on tariff rates, another important but related transformation is also happening; foreign capital is starting to come home. For decades, the United States ran large trade deficits, which were funded by foreign capital coming into the country; this foreign capital was invested in everything from U.S. Treasury securities to U.S. stocks, U.S. real estate, U.S. corporate bonds, and other U.S.-based assets. This flow of capital financed our consumption and held up the value of the dollar and U.S. financial assets. However, if the trade deficit shrinks, which is an explicit target of the Trump Administration, those capital inflows should also shrink. That’s just how the math for the balance of payments works.

So it appears to us that the world economy is moving away from the inexorable growth of global capital mobility that defined the last few decades of economic history. In the face of higher U.S. tariffs, demand from foreign buyers for U.S. financial assets should slacken, and more of that foreign capital may stay put overseas or leave the United States to head back home. That could mean lower U.S. asset prices and increasing asset prices abroad. As a result, betting only on U.S. stocks may not be the sure thing it once felt like. In fact, in the first quarter of 2025, foreign stock markets handily outperformed the S&P 500 — and that may not be a coincidence.

- Gold Revaluation

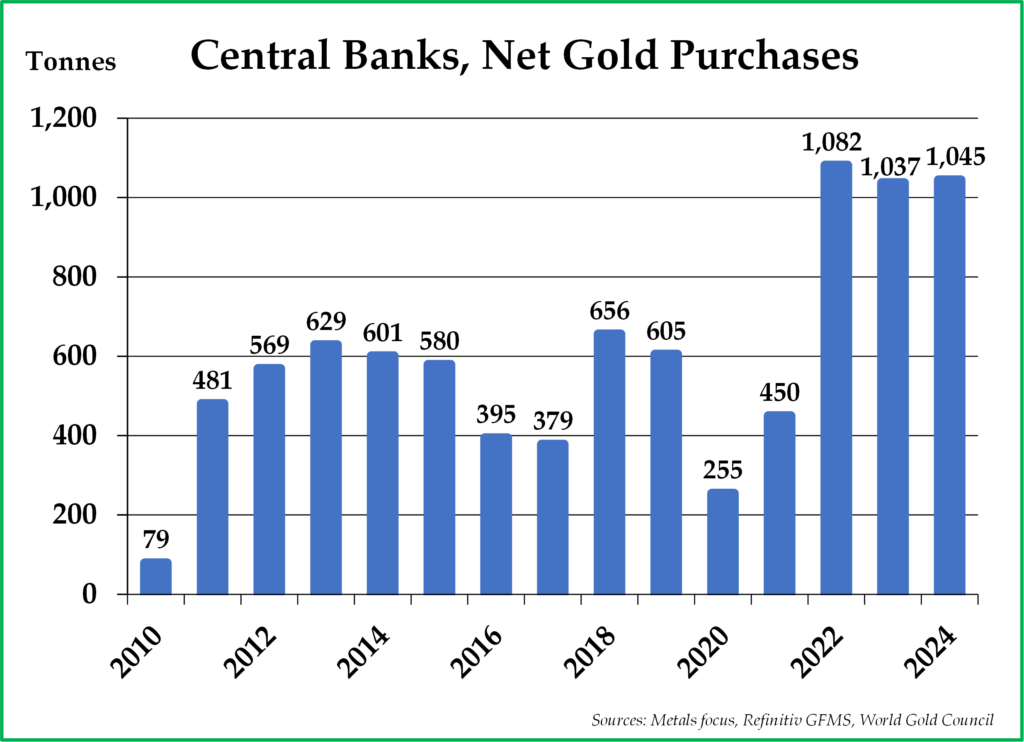

Gold has been quietly rallying due to increased demand from central banks. While the U.S. dollar and Treasuries have long served as the world’s reserve assets, it is now gold that is starting to glitter. Starting around 2014, foreign central banks stopped being net buyers of U.S. Treasuries, and the trend picked up speed after the United States and its allies froze Russia’s foreign government bond reserves in response to the Ukraine invasion. That move sent a loud signal to countries outside NATO: government bonds held abroad might not be as safe or as politically neutral as once thought. Not surprisingly, central banks started buying gold in size, especially in emerging markets. Unlike bonds, gold doesn’t come with counterparty risk or political strings attached.

At the same time, the BRICS countries have been working to settle trade in their own currencies and use gold to square things up, thus steering around the dollar entirely.1 And recently, U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has floated the idea that a weaker dollar could help U.S. industry, which is a goal that, whether directly or indirectly, could be helped along by a higher gold price. During President Trump’s first quarter back in office, gold rose by a whopping 20% while the U.S. dollar index fell by 4.4%. That kind of move simply doesn’t happen in a vacuum.

4. U.S. Federal Deficit Spending

The Federal government is spending far more than its tax receipts, and this deficit is widening, anomalously so, during a time of peace and a growing economy. Over the past few years, deficits have run between 6% and 8% of GDP, levels we used to see only in wartime or during deep recessions. A big part of the deficit problem is rising interest costs, which are starting to crowd out spending on things like defense, infrastructure, and other long-term investments. Fixing the widening deficit will be neither easy nor painless. It will take some combination of lower spending, higher taxes, inflation that reduces the real value of the debt, and/or even putting an artificial lid on interest rates to keep the government’s borrowing costs in check.2 However it plays out, the likely outcome is lower real interest rates over time, even in the face of persistently high rates of inflation. For investors, that kind of environment makes businesses with strong pricing power and real assets more attractive than bonds. In plain terms: owning an investment that can buy more stuff tomorrow is better than owning a promise to be paid back in dollars that buy less.

5. Defense Retrenchment

The United States has long played the role of the world’s security provider, but that model has started to become excessively expensive to many. With deficits running high and interest payments climbing fast, it makes sense for the United States to take a hard look at its global military footprint. Maintaining a strong military remains important, but the Federal government does not have endless resources. As the United States pulls back from some of its global commitments, the world may get a bit more unpredictable from political and economic perspectives. That means we are thinking more about geopolitical risk, the resilience of supply chains, and the value of owning real, durable assets in safe jurisdictions. In short: in a world with fewer guardrails, it’s wise to own things that may not depend on perfect regulatory, legal, trade, and/or other conditions.

When the rules of the game start to change, it may be prudent to own things that don’t rely on the old playbook. The trends that have defined markets over the past ten years will not be the trends that define the market of the coming decade. In 2030, we have high confidence that the ten largest market cap equities in the world will not be dominated only by U.S. technology stocks, as is the case today.

As a result, we continue to like the same asset classes that have worked during other periods when the world became a little wobbly: real assets, businesses with pricing power, and assets that don’t depend on central bank credibility to hold their value.

Areas we believe have long-term opportunity:

- Gold and other commodities: Unlike fiat currencies, they can’t be printed. And as more countries move away from dollar-based reserves, demand for gold may continue to rise.

- Real estate: Tangible, productive, and historically a solid hedge against inflation—especially in supply-constrained markets. Moreover, if real interest rates are negative, real estate owners will likely benefit from low financing rates on their mortgage debt.

- Foreign equities: Valuations are more attractive overseas, and when the dollar weakens, international stocks often do better. That’s a combination we like.

- Bitcoin (selectively): For highly risk-tolerant investors, Bitcoin is a digital asset with properties not unlike gold — limited supply, not tied to any government, and increasingly seen as a hedge against monetary disorder. The volatility of Bitcoin may not be palatable for many investors, however,

Areas where we are more cautious:

- Bonds: In a high-inflation world, bonds tend to perform poorly. They offer fixed returns in an environment where real purchasing power is anything but fixed.

- Broad U.S. stock indices: The S&P 500 is more top-heavy than ever, dominated by a handful of tech stocks trading at valuations that still assume everything will go right. That’s not a bet we’re comfortable making today.

As always, our goal isn’t to predict the future with precision—it’s to prepare for a range of high-probability outcomes. In times of great transition, owning real things tends to work better than owning fixed income investments. During such periods, volatility can be very high, and we would be surprised if the investing environment did not get worse than it is today before it eventually got better. And we are trying to position our client portfolios for such an environment.

*****

We are so grateful for your continued trust in asking us to be the steward of your assets, now more than ever. We are constantly learning and evolving and seeking investments that can help your capital survive and thrive during this unique period of upheaval.

Sincerely,

Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management

1BRICS is an acronym for the large emerging market economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

2We discussed the topic of yield curve control in our October 2023 quarterly commentary.

This commentary is prepared by Pekin Hardy Strauss, Inc. (dba Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management, “Pekin Hardy”) for informational purposes only and is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. The information contained herein is neither investment advice nor a legal opinion. The views expressed are those of the authors as of the date of publication of this report, and are subject to change at any time due to changes in market or economic conditions. Although information has been obtained from and is based upon sources Pekin Hardy believes to be reliable, we do not guarantee its accuracy. There are no assurances that any predicted results will actually occur. The S&P 500 Index includes a representative sample of 500 hundred companies in leading industries of the U.S. economy, focusing on the large-cap segment of the market.