“It fell to the floor, an exquisite thing, a small thing, that could upset balances and knock down a line of

small dominoes and then big dominoes and then gigantic dominoes, all down the years across time…It

couldn’t change things. Killing one butterfly couldn’t be that important? Could it?”

─ Ray Bradbury, “A Sound of Thunder”

In 1972, famed MIT meteorologist and chaos theorist Edward Norton Lorenz presented a research paper about how chaotic mathematical functions are very sensitive to initial conditions. He titled this well-renowned study “Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil Set Off a Tornado in Texas?” The gist of this analysis focused on the theory that slight variations in initial conditions can lead to dramatically different results. Over time, this hypothesis became known as the “Butterfly Effect,” and it has had wide-reaching influence, not just on meteorology and chaos theory but also on supply chain management, investments, and many other fields.

Today, many strange and not-so-strange shortages are popping up left and right, whether it be well-documented shortages (e.g., rental cars, bicycles, and semiconductor chips) or more mysterious shortages (e.g., Halloween candy, French fries, and Thanksgiving turkeys). And this problem is not just a domestic one. In the face of anemic economic growth, natural gas prices in Europe have quadrupled, coal prices in China stand at an eight-year high, and gasoline shortages in the United Kingdom are accelerating. At the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, it made intuitive sense for the world to run short of surgical masks, computer webcams, and hand sanitizer. 18 months later, despite the re-opening of the economy, consumers are experiencing surprisingly long lines, higher prices, limited choices, and constant references to amorphous “supply chain issues.” In too many cases, there is no stock available, and no idea when the product will be delivered.

It would be overly simplistic to just to blame the coronavirus, which has certainly contributed to the current series of global supply chain problems. In reality, the pandemic has often just exacerbated already existing issues. The conditions in place prior to the pandemic played important roles as economic “butterflies” in creating today’s shortages. Many of today’s supply chain issues can be associated with labor shortages, whether it be the labor necessary to make a product in a factory, receive a shipment of containers at a port, or transport shipments in a truck. Other significant and interlinked issues contributing to today’s shortages include transportation problems, deficient energy investment, excessive industry consolidation, and semiconductor issues.

Labor

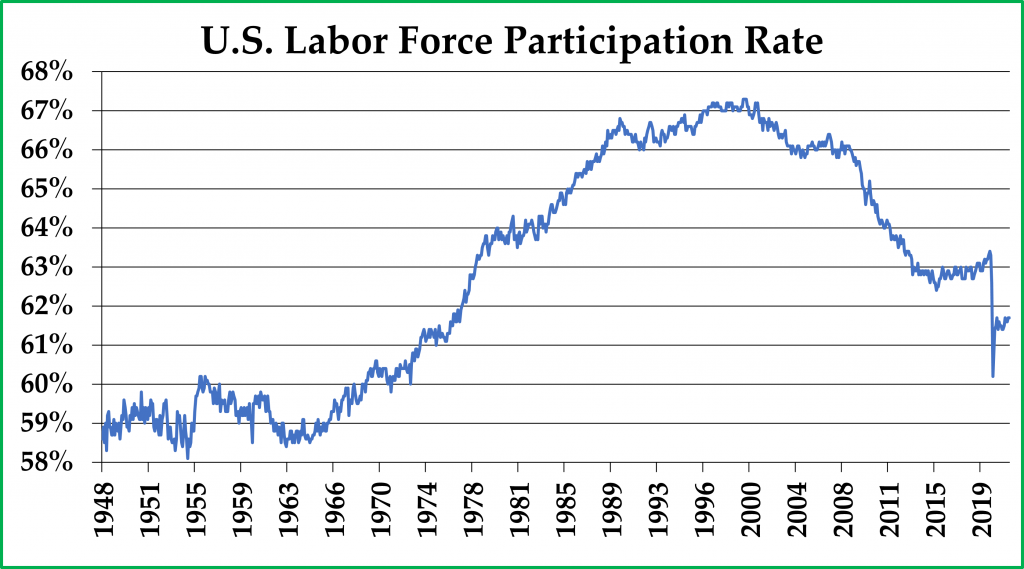

When the pandemic caused a hard shutdown of the economy in March 2020, the U.S. labor force participation rate plunged to its lowest level since 1973, when a far more significant proportion of families were one-income households compared to today. While the participation rate has recovered some from the March 2020 bottom, it has stubbornly remained below pre-pandemic levels. Notably, the labor force participation rate remains relatively low even in the face of significant pushes on the local level across the United States to increase minimum wages.

With the Delta variant causing a persistent risk of coronavirus infections, companies are struggling to hire workers. Federal jobless benefits and continued childcare obligations may be acting as obstacles in preventing many workers from re-entering the labor force. Additionally, some workers have decided to switch careers during the pandemic or retire early after a layoff. Others are quitting jobs that require them to work full-time in physical offices. Roughly 10,000 Baby Boomers have been retiring each day, and that trend certainly has not slowed during the pandemic. The combination of all these factors and recent deglobalization trends suggest that the days of plentiful and inexpensive labor may be in the past.

Transportation

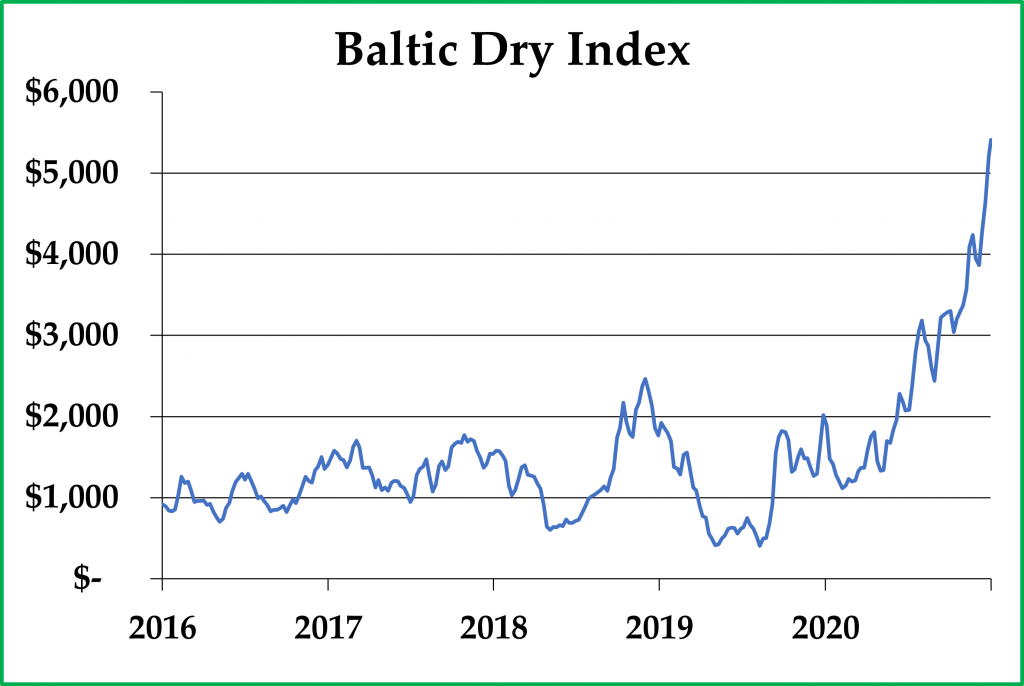

A series of events have disrupted the world’s well-oiled supply chain systems, causing transportation bottlenecks on land and sea. In March 2021, the week-long blockage in the Suez Canal halted shipping traffic on a vital transportation waterway that links Europe to Asia. Roughly l2% of global trade, ~1 million barrels of oil and approximately 8% of the world’s liquified natural gas pass through the Suez Canal each day – all of which ground to a rapid halt. A series of temporary coronavirus-related closures of key ports in China and Vietnam have strained product exports over the past 18 months. As of this writing, more than 70 container ships are idling offshore the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach because there are not enough dockworkers to unload the cargo, nor are there enough truck drivers to transport the goods. As demonstrated in the chart to the right, these transportation disruptions have caused container shipping costs to more than quadruple as compared to last year.[1] The pandemic has highlighted that optimized supply chains, while highly efficient in most conditions, can prove to be inherently fragile in times of extreme dislocation.

Energy

With relatively low oil and gas prices over the past six years, traditional exploration and production companies have materially curtailed capital investment. However, today’s energy shortages cannot be blamed merely on the lack of investment. Last year, a cold winter in Europe caused energy storage facilities to be drawn down to lower than normal levels. Prices for other commodities like coal have been rising, making it cost-prohibitive for power producers to switch input fuels. Increased weather volatility has further contributed to the problem; one reason why oil and gas supplies are low is the damage that Hurricane Ida did to the energy infrastructure in the Gulf of Mexico.

The labor shortages bedeviling the world are affecting the energy markets. In the United Kingdom, the number of available truckers as compared to the total need for truckers stands at a ratio of 1:8, largely attributed to a scarcity of labor caused by Brexit; most truckers were forced to leave the United Kingdom after Brexit because they were not U.K. citizens. As a result, the United Kingdom is experiencing shocking gasoline shortages and ridiculously long lines. Until the United Kingdom increases wages sufficient to attract domestic workers to trucking jobs, these shortages should remain in place.

Energy shortages exacerbate other problems, which, in turn, create additional, cascading supply chain constraints. These shortages prevent products from being transported, stop workers from getting to their jobs, cause unplanned production shutdowns, and generally make it difficult for companies to resolve their supply chain shortages.

Industry Concentration

In the past, we have written about corporate consolidation. As a result of decades of lax antitrust enforcement, corporate concentration has increased in virtually every industry, including airlines, wireless telecom services, cable television, hospitals, medical insurance, social media, semiconductors, and others. In our view, the level of corporate concentration in specific industries has contributed to today’s shortages.

For example, in the bicycle components industry, Japan-based Shimano boasts ~70% of global market share for components for bicycles that cost more than $500. With the massive spike in demand for bicycles over the past 18 months, both Shimano and SRAM, Shimano’s primary competitor, have shown that they simply do not have sufficient production capacity to supply their customers. As a result, bicycle and bicycle component shortages are commonplace. Should there have been a more fragmented industry, the extent to which shortages have occurred would have been far more limited.

Semiconductors

Beyond shipping, energy, and labor, the world is faced with a serious semiconductor chip shortage, driven by four key factors. First, the pandemic exacerbated supply chain issues by disrupting semiconductor production just as the global demand for electronic products surged. Second, semiconductor producers projected too little demand during the pandemic. Companies that cut back on semiconductor orders during the pandemic were subsequently forced to go to the end of the production line. Third, semiconductor chips are used in a wide array of products, including computing devices, cell phones, tablets, home appliances, cars, and gaming consoles. All of these product categories experienced a spike in demand. Furthermore, demand materially increased for certain new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, cloud computing, and 5G cellular networks — all areas that require an increasing number of chips. Semiconductor demand in 2021 has jumped by nearly 50%. Fourth, over the past few years, there has been a secular trend of outsourcing production to chip foundry companies like Taiwan Semiconductor. These foundry companies were already working at full capacity prior to the pandemic, and funding and building a new semiconductor fab is a five-year process. Adding new semiconductor production capacity requires massive investment, deep technological know-how, and enormous amounts of time. Like the bicycle components industry, the availability of semiconductor chips has been affected by extreme industry concentration within the semiconductor industry.

Accordingly, current lead times for many semiconductor parts are roughly one year out, which should cause widespread shortages of many electronic products (e.g., cars, washing machines, dishwashers, televisions) that could persist for at least a year, if not longer.

Investment Implications

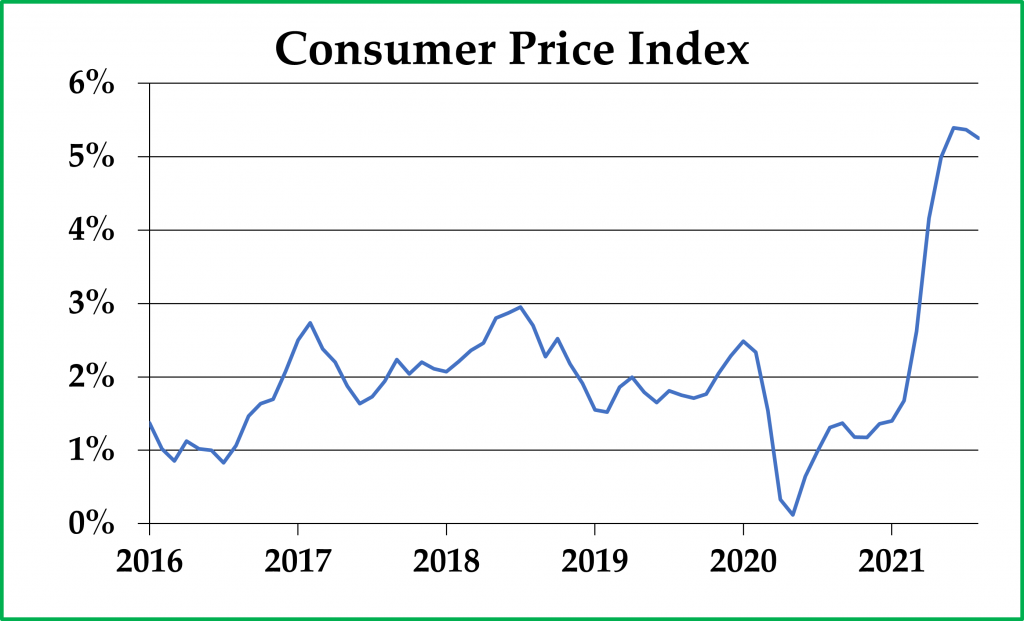

Should these shortages dissipate sooner rather than later, inventory levels, employment levels, and out-of-stock rates will revert to historical averages. However, countries have started to erect walled gardens around their economies, and shortages and inflationary forces may become far more common. If we are entering a more permanent environment where shortages become commonplace, the long-term impact on the markets, the dollar, and the broader economy will be consequential.

Equities

Companies like Walmart, Amazon, Target, and FedEx have either warned about the impact of rising labor costs on profitability and/or have started to offer material compensation adjustments to address growing labor shortages. Not only will corporations have to pay more in labor expenses, but they also will be forced to pay more to produce goods and transport them. Companies with strong brands that sell products with inelastic demand should be able to pass on the added costs to their clients without too much pushback. Large companies are less likely to have supply chain disruptions than smaller companies, as their suppliers are likely to focus on maintaining solid relationships with their most important customers.[2]

To reduce the risk of supply chain problems going forward, we expect companies to tighten their supply chains, bring more production closer to home, and increase safety inventory levels. These changes will increase costs and require additional funds to be held in working capital, thus reducing returns on capital going forward.

Such corporate adjustments would represent significant shifts from the ongoing trends of the last several decades, when global supply chains, just-in-time inventory systems, and a general lack of shortages dominated the economic landscape. Such changes would cause additional inflation, causing companies that market discretionary products to be disproportionally hurt. In contrast, companies that sell necessities (energy, consumer staples, food, etc.) should increase their share of consumers’ wallets as consumers adjust their budgets accordingly.

Bonds

Accelerating inflation should be negative for bond prices: however, we anticipate that the Federal Reserve and central bankers across the globe will continue their aggressive monetary policy to keep bond yields low and bond prices high for as long as feasible. Looking forward, we would anticipate low single-digit investment returns at best from bond investments over the near-term. After adjusting for inflation, we expect investment-grade bond returns to be below 0%. As a result, we have been aggressively looking for alternative investment ideas in an era of low-yielding bonds.

Gold

Historically, rising inflation and financial dislocation are bullish trends for the price of gold. Surprisingly, gold prices have declined thus far this year after enjoying an outstanding year in 2020. We do not believe that interest rates will be rising significantly any time soon for the reasons stated above, and, therefore, we view the recent weakness in gold prices as a buying opportunity.

******

We thank all of our clients for their continued support in the management of their investable assets. Should you have any questions about the contents of this letter, please do not hesitate to reach out to us.

Sincerely,

Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management

[1] The Baltic Dry Index is an index of average prices paid for the transport of dry bulk materials across more than 20 global routes.

[2] One anecdotal piece of evidence that supports this theory is Walmart’s requirement of its suppliers to deliver 98% of products on time; otherwise, the supplier will be forced to pay a penalty of 3% of cost of sales to Walmart. One can assume that shortages at Walmart will be less than those occurring at other retail chains.

This article is prepared by Pekin Hardy Strauss, Inc. (“Pekin Hardy”, dba Pekin Hardy Strauss Wealth Management) for informational purposes only. The information and data in this article do not constitute legal, tax, accounting, investment or other professional advice. The views expressed are those of the author(s) as of the date of publication of this report, and are subject to change at any time due to changes in market or economic conditions. There is no guarantee that the types of investments discussed herein will outperform any other investments in the future. Although information has been obtained from and is based upon sources Pekin Hardy believes to be reliable, we do not guarantee its accuracy. There are no assurances that any predicted results will actually occur. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is an unmanaged index representing the rate of the inflation of U.S. consumer prices as determined by the U.S. Department of Labor Statistics.